Historical or Hysterical? Reading Babi Yar and The White Hotel

- Yiddish Shmoozers in Translation

- Jan 6, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Jan 9, 2024

Sunday, January 7, 2024, 3-4:30 pm Pacific

The "double header" of Babi Yar and The White Hotel as an intertextual pairing has given me and our two guest discussion leaders, psychologist Dr. Claudia Kohner and literary scholar Dr. Andrea White, almost too much to think about. Are two or three heads better than one? We hope you think so!

Introduction (Gelya Frank):

I'm offering here some framing thoughts, leading to the essay by Andrea in conversation with Claudia based on a close reading of The White Hotel's manifest and latent content. The essay is followed by questions for discussion. To start off, Claudia is interested to hear how readers first became aware of the genocide that took place at Babi Yar in the fall of 1941. She asks whether American readers, like herself, first became aware of the Babi Yar massacre only as late as 1981, when the novel The White Hotel appeared. Why was Babi Yar not on the radar of so many otherwise interested readers? Andrea picks up this question in her essay, where she proposes to put The White Hotel in a literary historical context of works by survivors concerning the Holocaust--that is, the appearance of a literature of witness.

Reading scholars, critics, and interviews with D. M. Thomas, the three of us (Andrea, Claudia, and Gelya) are taken with the author's interest in the question of hysteria and, in particular, with the premise or proposition that events such as at Babi Yar can be read as locations of mass hysteria, sites where personal and social symptomatology express themselves in parallel, if not interconnected ways. In my brief comments here, I take the role of a "disobedient reader" who questions Thomas's use of a female patient Lisa Erdman as the symbolic carrier of the personal hysterical symptoms (unexplained pains in her breast and groin) that, by the end of the book, the author reveals as having been "caused" by events that happen later in time. This book offers a mystical, poetic, atemporal transubstantiation of a half-Jewish character's suffering--and her brutal death on earth in a Nazi genocide-- and the resolution of her psychological conflicts in a Christian-like afterlife (set in Israel!) where the sun shines and loved ones meet again. Do you buy it?

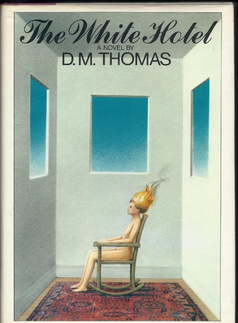

In the gallery of images above, who is the mysterious woman who in fact historically links The White Hotel with Babi Yar? Surely not the opera singer Lisa Erdman, the fictional patient treated by Dr. Sigmund Freud in The White Hotel. Fictional characters, like ghosts, do not lend themselves to photographic likenesses. Rather, the woman pictured between Anatoly Kuznetsov's "documentary novel" Babi Yar and D. M. Thomas's fictional psychoanalytic case history is Dina Mironovna Pronicheva (1911-1977). Her physical suffering--including having been stomped on the breast and hand by hob-nail booted Nazi gunmen-- is revealed late in Thomas's book to be the temporally dislocated cause of the patient Lisa Erdman's "hysterical" symptoms. Whereas Pronicheva actually survived, however, her fictional incarnation as Lisa Erdman dies at Babi Yar. What purpose and vision of Thomas's theme does the death of Lisa/Dina serve?

Dina Pronicheva, a Soviet trained actress in the Kiev puppet theatre, was thought to be the sole survivor among the 30,000 Ukrainian Jews rounded up and massacred by the Nazi army at the Babi Yar ravine on Yom Kippur, September 29-30, 1941. Not only was Pronicheva's first-person account, as heard by Kuznetsov, the basis for the descriptions of murder, rape and other atrocities in his chapter Babi Yar (pp. 89-110). Pronicheva's resolute nine-minute testimony was captured on film in Russian and can be seen on YouTube with English subtitles at the Soviet trial in Kiev on January 24, 1946 of case No. 1679 "On the atrocities committed by fascist invaders on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR." A simple Google search of Dina Pronicheva turns up the YouTube material and various versions of Pronicheva's written testimony in Russian and in English translation.

In my opinion, these sources by and about Pronicheva are well-worth finding online and thinking about. Historians' responses to the different versions of Pronicheva's testimony, it appears, have focused on questions of the historical credibility of her accounts, given the differences (the so-called "contradictions") she introduced under differing circumstances over time. When The White Hotel was published in 1981, critics also jumped on a textual controversy but of a literary rather than historical nature--i.e., whether author D. M. Thomas plagiarized the chapter titled Babi Yar in Kuznetsov's book. We can ask, if there were a misdeed on author Thomas's part, does it involve a literary crime against the earlier author Kuznetsov? Or, instead, was there a historical, cultural, and even moral crime in Thomas's corruption of Pronicheva's testimony as a survivor? Again, why is it important to the book that Lisa dies at Babi Yar rather than survives? Thomas disregards the historicity of Jewish survival in favor of a conceit about humankind's struggle in Freudian terms between Eros and Thanatos.

This leads me to the more general and important question. A decade into the second wave of feminism when the book was published, what symbolic weight is carried by the character of Lisa in The White Hotel? Why is it necessary that it be a female who suffers? That she suffers from symptoms in her body's sexual zones? And that she must die? Lisa's life and death are the field on which, in Thomas-cum-Freud's world, Man's most destructive impulses play out as "mass hysteria." I say "Man" with a deliberate capital "M," because the gender binary embedded in The White Hotel portrays war as the business of men, a business that propels the Western literary canon from its beginnings in the Trojan Wars (Odysseus, The Aeneid) to today.

Essay (Andrea White)

As many have observed, a new literary genre emerged after the Holocaust, the literature of witness, that could speak of those incomprehensible and unspeakable events as told by subjective witnesses. Some took the form of daily journal entries – Anne Frank’s, Victor Klemperer’s, for example. Some took the form of documentary accounts written after the fact, such as by Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel.

A novel about the Holocaust seemed a trickier proposition, mixing fiction with horrific facts, but semi-fictional accounts started emerging as well. But not right away. In fact most people wanted to put the war years behind them and few publishers felt there was an audience for what survivors wanted to say. Even the left wing publisher Einaudi refused to publish Primo Levi’s This is a Man in 1946. It wasn’t published until 1959 and didn’t sell well until 20 years later. Chava Rosenfarb’s masterful three volume novel The Tree of Life that we read together over several sessions movingly tells the story of the Lodz ghetto where she and her family were imprisoned. It wasn’t published until 1971, first in the original Yiddish. It didn't appear in English until 1985. Thanks to the tireless persistence of her daughter and translator, literary scholar Goldie Morgantaler, Rosenfarb's work is finally getting recognition in North America and, importantly, as of 2023, in Poland.

Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar, seems a late-comer, its English translation appearing in 1970. It would have been published in 1966, if Soviet censorship had not held it up. In fact its uncensored publication was only possible when Kuznetsov defected to London and smuggled his manuscript with him. He describes his work as “a document in the form of a novel” and himself as “a crafter of memory.” In order to avoid the eclipsing of the catastrophes of the 20th century, he writes in his Preface, these events must be remembered, especially in light of the absence of a monument that clearly memorializes the horrors of Babi Yar.

Comments